Welcome! This is not a page I expect most people to visit. What could be more dry than statistics about water usage, which government department manages water, what is the process for the development of big infrastructure projects and how many labor voters lived in the Kangaloon electorate?

“Not much” I hear you think. Well this was precisely the information everyone who fought this water war had understand and be conversant in as well as the hydrology and ecology of the aquifer.

Where did Sydney’s Water Come From?

Out of a tap, where else? There are a lot of factors in getting it to our taps; logistics, infrastructure, finance and politics all play a big part.

The government owned corporation, Sydney Water Corporation is responsible for providing clean potable drinking water for Sydney and also manages wastewater and storm water. In 1999, in response to a major contamination of fresh water in Warragamba Dam, the role of catchment and supply was divided, and the Sydney Catchment Authority (SCA) was created to manage the catchment areas, dams and raw water. Water is collected and stored in 21 dams throughout a catchment area of more than 16000 square km (35), which is then sold, under a commercial agreement, to Sydney Water, Shoalhaven and Wingecarribee Councils, who treat it and deliver it to taps across Sydney, the Illawarra and the Blue Mountains. (44) This is important, because the division of water supply into a wholesale and retail division was the initial step in the partial privatization of water supply in NSW. (45)

Sydney has one of the highest per capita storage capacitiesin the world, (46) however, in 2003, despite being in the middle of a drought, Sydney was using 600 million litres of water, 106% of the annual sustianable yeild of its water supplies, so the NSW government responded with the development of strategies to address the future of secure water supply and sustainable use. (47)

Planning to Drought Proof Sydney

Action was taken to initiate the 5 major projects which the government had announced. These included: accessing “deep water” in some of the dams, transferring more water from Tallowa Dam in the Shoalhaven, constructing a desalination plant in Sydney, implementing large scale recycling programs for new land release areas and sinking large bores to extract groundwater to augment existing dam supplies. Part 2 of the plan was to introduce a range of water conservation methods across homes and businesses.(47)

In the 5 project plan, only the first project didn’t draw the Government into a battle. The SCA identified possible groundwater sites suitable for large scale water extraction. The Kangaloon site yielded promising results, so this option was pursued.

The SCA required no permits to carry out such investigations, and in their own Groundwater Investigation (2006) stated that “any groundwater investigation can be assessed and determined by the SCA pursuant to Part 5 of the EP & A Act unless the proposal is one that is likely to have significant environmental effect”. So having already decided that there would be no significant environmental effect, test pumping from the aquifer went ahead.

In particular, for the Kangaloon Borefeild project, there is a significant part of the NSW Environmental Planning and assessment Act 1979 which disempowered the community. Look up any environmentally contentious issue in NSW, and you will find references to the dreaded “PART 3A”. This section is now being repealed, (48) but this controversial act introduced in 2005, allowed fast tracking of major projects via bypassing local councils and normal assessment routes, going straight to the minister for planning. It put the community and government at odds due to the less rigorous requirements of developers (including the SCA) to carry out detailed environmental studies and community consultation. Further, there was no avenue for appeal once approval had been granted via “3A” (49)

And what about adherence to the National Water Initiative? There was no consideration of the central issue of sustainable extraction and the avoidance of overallocation of resources, especially considering the 2004 embargo on further groundwater extraction from the aquifer due to overextraction by local landowners. (51) Not enough water to share amongst farmers but enough for Sydney?

Community Consultation, a Necessary Evil!

As part of the process of community consultation, a “Community Reference Group” (CRG) was established to “form a communication channel between government and the broader community”. The minutes of these meetings clearly show, even from the first meeting, where the terms of reference were presented to the group, the power balance between a big government organisation and the small but diverse group of community participants. The CRG had it’s first meeting in June, submissions on the groundwater project were to be received by mid August, just 2 months.

Concerns voiced by participants included:

- whether the decision to extract groundwater was a fait-accompli and the amount of influence the CRG had to determine how water should be extracted or managed

- whether the voice of the CRG had any innfluence on government intentions to use groundwater

- what was the purpose of undertaking environmental assessment and the role of CRG when government had clearly indicated its commitment to use groundwater

- the strong sentiment in the community that the consultation was too late, and that if consultation had commenced earlier, different decisions may now be under consideration

- that there was no role for the local council to determine the proposal because it would be assessed as a “state significant development” (20)

These are probably not too different from the feelings many communities have when faced with a big development which will effect them in many different ways.

In the ensuing battle, many issues were raised, mostly pertaining to the fairness of the process, the validity of the science, independence and imparitality of the scientific studies the transparency of the project and , conflicts of interest in the process of engaging of consultancy firms producing the reports, and of primary concern to the local residents, was that their long and short term interests were being overlooked to solve a short term but recurring political issue of drought water management. (20)

Adversarial Politics, Problems for Local Members in Opposition

The State member representing Kangaloon, Pru Goward was a member of the opposition, but raised the issue of Kangallon in her inagural speech to the NSW Parliament, ”

“In the Southern Highlands, the Government’s determination to take water from the Kangaloon aquifer to boost Sydney’s poorly planned supply has many fearful for the loss of forest and productive farmland. Why is so much put at risk for so little, and at such a price? Our farmers deserve better than this” (51)

In later representation, she argued, “To go ahead with a project possessed of such manifestly significant question marks means it fails the first test of sustainable policy: it fails the precautionary principle test. ..” (52)

However, the state government was not to be swayed, there was an election looming, several million voters in Sydney without water posed a bigger threat to staying in power than a few thousand angry Liberal voters from the bush.

Fairness in Governance, Finding New Ways Forward

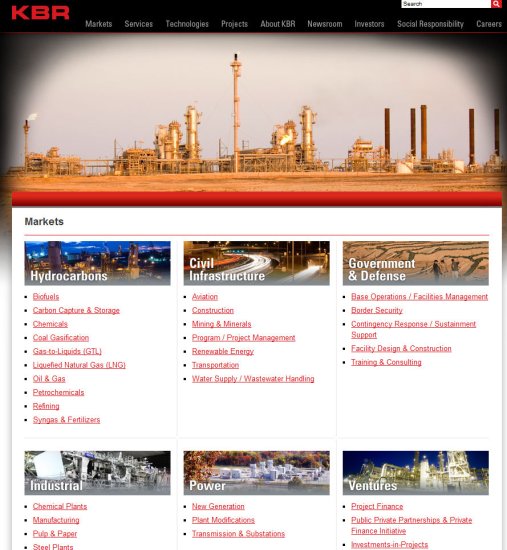

Homepage of KRB, commissioned to conduct EA for Borefield Project Click for More Thoughts on This One

The increasing demand for water resources has the potential to create conflict between the many different users of water. In Australia, the drought brought the issue of water management and water sharing to the forefront and as a result, public awareness of water has greatly increased. At a government level, there are now guidelines for the many different departments involved in water management to ensure “fair distribution” of water, so that water can be shared between all users and the environment, that the health of river systems can be maintained, the social and econominc needs of regional communities are met, and cultural needs such as recreation or indigeonous cultural uses can also be facilitated. Groundwater use is a more recent factor in planning, but there are guidelines for sharing plans for aquifer water, which has very specific rules to ensure the protction of the environment associated with an aquifer and the aquifer itself. (53)

These documents leave the reader feeling that everything has been considered and planned for in Australia, there should be no cause for conflict. But on almost every document, there is an “out clause” for projects of a special or complex nature, such as the Snowy Mountains, for which there will be other planning processes. The Kangaloon Aquifer was one such project, which needed no environmental assessment or permissions in order to start the project, and was able to bypass the usual route for assessment by the “3A loophole” which sent it straight to the minister for planning to be rubber stamped.

It is projects of this nature that are causing conflict, but now in the growing awareness of the complexity of water management, mainstream media has entered the discussion on the need for water reform, the growing recognition of the failure to of applying free market principles to the management of essential natural resources, and the leaving of crucial decisions about water distribution to entities who’s priority is profit, rather than socially and environmentally responsible water use. (54) (Companies such as KBR, for example?)

Future Prospects

In the case of the Kangaloon Aquifer water war, 6 years has passed since the proposal was in the spotlight. What ended that fight was government intervention at federal level and the end of the drought. But as we head into another El Nino phase, and inevitably another drought leads to water shortages, this issue will be raised, and no doubt another fight will ensue.

My observation is that since a halt was put to the project, the SCA has continued with it’s planning, Environmental Assessments, property acquisitions, buying local water allocations and drilling bore holes. It has it’s ducks in a row, ready to mobilise as soon as there is a need.

Opponents to the project however, have had ceremonial burnings of their archives in the misplaced assumption that the issue has been laid to rest. What they will have though, is a significant amount of study into the hydrology and ecology of the area which has been carried out in the more appropriate time frame which would appear to support the case that large scale drawdown of groundwater from the aquifer is not advisable at many levels. How this will be dealt with politically and institutionally will be closely watched!